Story #007

I Spy With My Little Eye…

Max J Miller

I Spy with My Little Eye…

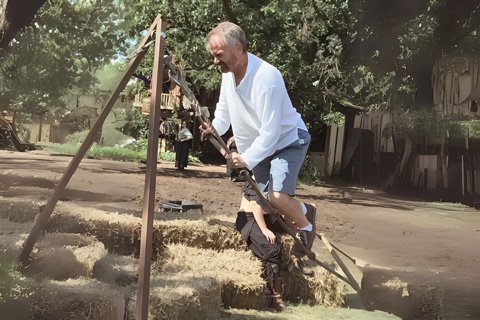

When we moved to a new town in sixth grade, I made what seemed like a brilliant plan to acquire friends: join the Boy Scouts. Because nothing says “popular kid material” quite like a scrawny, clueless newcomer in a uniform with more badges to earn than I had skills.

My first month culminated in a “Camporee,” which sounds adorable but turns out to be a ruthless competition of outdoor skills. The other scouts arrive looking like mini Bear Gryllses, while I show up wondering if “s’more assembly” might count as an event I could actually win.

Not only was I brand new to Scouts, I was short for my age (11), and most of the Scouts my age had joined a year earlier. In every way an underdog, for most events, I was an onlooker at best. I tried to avoid getting in the way.

When it was my patrol’s turn to set up a tent, we gathered around a pile of canvas, rope, and poles, waiting for the signal to begin. “Go!” came the command, and the guys dove in like wolves on new prey.

In the frenzy, one of the guys handed me a pole and grunted, “Hold this!”

The tent rose in seconds, and then I saw the guys looking around in a panic. “He’s got it!” one shouted, and all eyes suddenly trained on me. “The pole, dummy! Give it to me!”

He grabbed the pole from my hands and within a few more seconds, he shouted, “Tent up!”

The scout leader said we should work together to make up the time. Obviously, his remarks were aimed at me, and I imagined the guys thinking ‘the new kid’ was to blame.

Looking back, I realize I couldn’t have known how to help my team, but I remember how helpless I felt then.

Our next event was a ‘circuit race’ involving several obstacles spread throughout the camp. I did my best to stay out of the way and to keep up with my patrol.

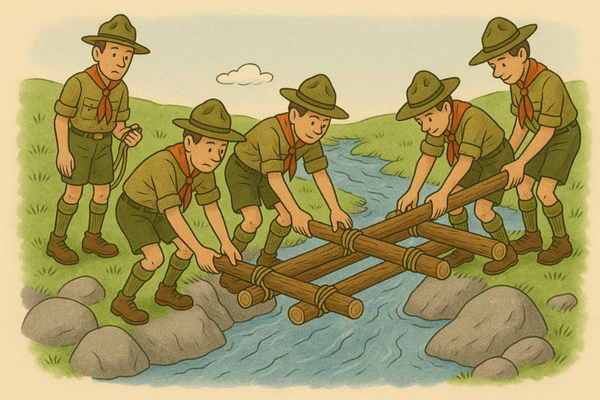

At one point, we followed a trail through some woods to a river’s edge. A scout leader there gave us some instructions: “Build a bridge that enables your team to cross the river safely. You can use any materials you have or find on the ground. Don’t damage any trees or plants.”

We spotted several logs close by, but they didn’t reach across the river. We had a few lengths of rope between us. The guys debated the merits of different approaches, while I stood back, observing the chaos.

I noticed the river narrowed around some big rocks a hundred feet downstream. I thought about it for quite a while without saying anything.

“They already think you’re an idiot,” I thought, “So don’t say a word!”

The guys began expressing frustration and seemed ready to give up.

Timidly, I spoke up. “Does the bridge have to be built here?”

“Where else would we build it, out in the parking lot?” came a snippy reply. The other guys laughed and made sarcastic comments.

“This is where the logs are,” one declared. He glanced at the scout leader for some kind of confirmation.

“The river narrows over there by those rocks,” I said, shrugging my shoulders.

“We have to build it here, right?” our patrol leader asked the scout leader.

The scout leader raised his eyebrows and cocked his head indicating he wasn’t going to give a direct answer.

Suddenly, the guys scrambled to grab the logs and headed toward the rocks.

I glanced over at our scout leader before I ran after them. He smiled and nodded in my direction with a wink.

By the time I got to the rocks, three guys were on the other side of the river, drenched from walking through the water. Two guys were furiously lashing the logs together, and two others positioned smaller rocks under the logs to stabilize them.

In minutes, all eight of us stood on the other side of the river doing a happy dance.

The scout leader shouted to us, “Head up to the barn for your next challenge—and hustle! You have a good shot to win this race!”

That evening, the scout leader from the bridge walked over to me. “You did well today.”

“It’s my first campout and I feel kinda stupid,” I replied.

“You’re not stupid, Max. I’d say you were the MVP for the winning Patrol today,” he said, patting my shoulder.

“Really?” I replied, looking around as if he might be talking to someone else. “But I didn’t do anything.”

“You asked an important question,” he said, leaning in. “When everyone else was stuck thinking about how to get the bridge built there, you were the only one who questioned the instructions. None of the other patrols finished their bridges. That’s not being dumb, Max. That’s being smart in the way that matters most.”

I let his words sink in. “I almost didn’t say anything,” I admitted. “This voice in my head told me to keep quiet, that my idea was probably stupid.”

He nodded knowingly. “We all have that voice. You’ll never get rid of it—the trick is learning when to tell it to shut up.”

The next morning at breakfast, instead of sitting alone, I found myself wedged between two patrol members who were already planning our next adventure. As they debated the best way to cook bacon over a campfire, I felt something I hadn’t expected to find so quickly in this new town: belonging.

Over the years, I’ve faced that inner critic countless times. Sometimes I surrender to its whispers of doubt, and those are the moments I regret. But when I’ve found the courage to speak up despite it, those are the moments that have changed everything.

Little did anyone know back then (especially me) that the “new kid” would deploy those secret weapons of curiosity and courage to become an Eagle Scout, a Scout camp counselor, and even a national leader in Scouting.

And it all started with one simple question about a bridge.

“The Sin of Certainty”

We’re adding a new feature to The Wisdom Wayfinder this week. It’s called Ideas Worth Shredding, and yes, it’s a spoof of TED’s tag line, “Ideas Worth Spreading.” I hope you’ll find it both thought-provoking and a little bit amusing.

But beneath the wit is a serious purpose.

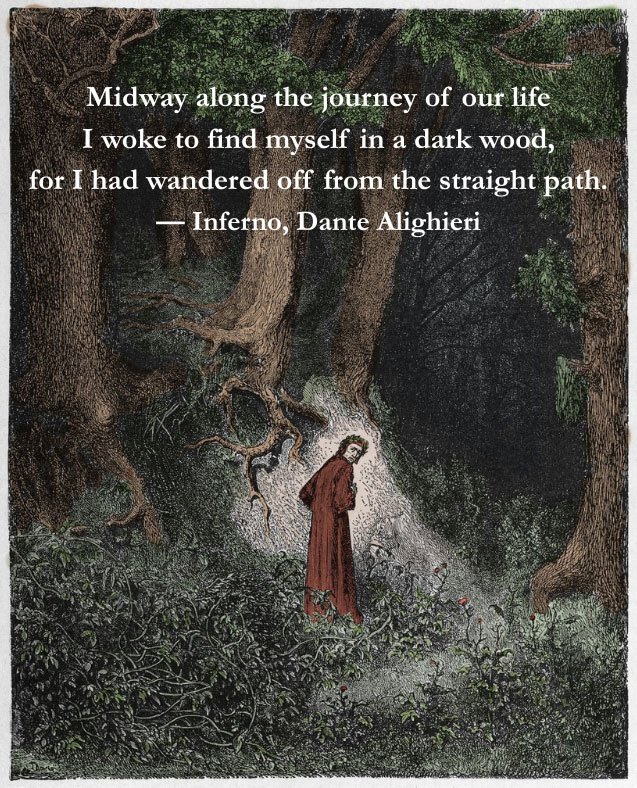

Over the past few decades, much of my personal growth and spiritual practice has boiled down to a single insight—captured best in a quote often attributed to Will Rogers:

“It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you in trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

Most of the suffering I’ve experienced hasn’t come from ignorance—it’s come from believing things that were never really true. I picked up these ideas along the way—about success, identity, love, even God. Some of them were once useful, but no longer serve me. Others never did. They held me back, distorted my perception, and limited my freedom.

Psychologists have identified over forty cognitive biases that influence how we perceive the world. Which only confirms something my stepfather used to tell me:

“You’re full of s#!+, and so is everyone else, but you’re better off knowing it.”

False beliefs don’t just hurt us personally. They poison our relationships. What lies at the root of most conflicts between spouses, neighbors, or nations? Isn’t it often our inability to question our own assumptions? To suspend certainty long enough to consider another’s experience?

In the recent film Conclave, Ralph Fiennes’ character, Cardinal Lawrence, delivers a haunting line:

“There is one sin I have come to fear above all else: certainty. If there were only certainty and no doubt, there would be no mystery—and therefore, no need for faith.”

I would go even further.

In the book of Genesis, humanity is said to live under a mysterious curse that stems from eating the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. Theologians debate what that curse is. I’m no theologian, but here’s my take:

The curse isn’t ignorance, but misunderstanding.

It’s arrogance.

The kind that clings to what it knows for sure, even when it’s wrong.

One of Jesus’ most repeated expressions reinforces this idea: the truth will set you free. The word truth in that passage is the Greek word aletheia, meaning unconcealed (revealed, exposed, uncovered).

That expression always makes me think of Toto pulling back the curtain to expose the little man pretending to be the Wizard of Oz. Unconcealing a certainty that hides a lie leads to freedom and peace.

Ideas Worth Shredding is an invitation to question those certainties. Not just to laugh at them, but to let them go—so something wiser, freer, and more loving can take their place.

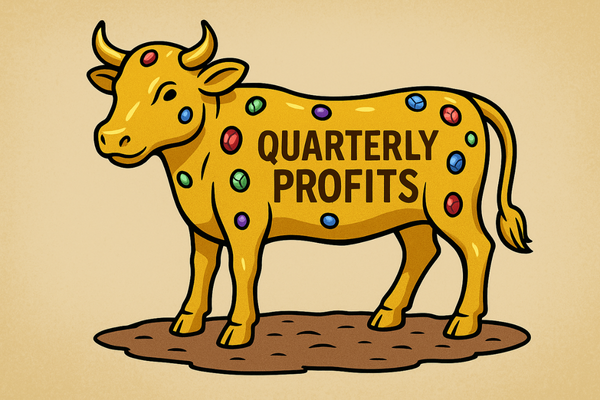

The Lie That Hollowed Business: “Profit Is Our Purpose”

A dangerous idea is so deeply ingrained in our culture that it’s almost invisible. It fizzes through boardrooms, business schools, and Sunday talk shows like a dissolving tablet vanishing into water. Its presence is so total we stop questioning it.

The idea?

That the purpose of business is to make a profit.

It sounds self-evident. Sensible. Responsible, even. But it’s false and quietly corroding the soul of enterprise.

Let’s go back to capitalism’s founding thinker, Adam Smith. In The Wealth of Nations, Smith spoke of profit and capital as the means of production. Means, not ends—tools, not telos. The fundamental aim of business, Smith insisted, was to serve: to meet needs, to solve problems, to create value that sustains and uplifts society. And if a company ceases to do that? Smith wrote that it should no longer exist.

Think about that.

Business is born of purpose, not profit. Profit allows purpose to scale; it’s fuel for the mission, not the mission itself.

And yet, somewhere along the way, we got it backwards.

Instead of asking, “How can we serve?” We started asking, “How can we survive?” We replaced value creation with shareholder value. We propped up institutions long after their purpose had withered—so long as they remained “profitable.” We started worshipping the golden calf of quarterly earnings.

The consequences aren’t abstract.

When survival trumps service, something dies. The spirit of the institution decays. The work becomes hollow. People burn out, disengage, and lose faith—not just in companies, but in capitalism itself.

Theologian Walter Wink referred to this inversion as “The Fall”—not just of individuals but also of institutions. The fall occurs when a person or entity prioritizes survival over their calling. The moment it chooses self-preservation over purpose, it begins to rot from within. It loses its soul.

But redemption is possible. Wink said redemption is the return to one’s calling. What is a calling? Wink says each of us has something unique to contribute to the well-being of others. To be about the business of making that contribution is what it means to follow our calling.

The same holds for business. When an organization remembers why it exists—not just to grow but to give—it comes back to life. The spark returns. Energy flows. People reconnect with the joy of meaningful contribution.

Yes, this sounds spiritual because it is.

The ancient wisdom holds: Seek first the kingdom… and all these things will be added unto you. In modern terms: prioritize your purpose, and the profit will follow. But that requires courage. It requires faith in your mission, the people you serve, and the idea that there’s a deeper order than just dollars and cents.

So let’s be clear:

Profit is not the purpose. It’s the byproduct.

Purpose is what dignifies the work.

And when purpose leads, prosperity follows.

Let’s remember why we started.

Let’s call business back to its soul.

You’ve heard it said, “The purpose of business is profit.” That’s an idea worth shredding.

Cheers,

P.S. This Wayfinder was longer than usual. I hope you found it valuable. Please feel free to hit “reply” and let me know what you found meaningful.

P.P.S. Have you discovered an “idea worth shredding?” Click here to submit it for consideration for The Wisdom Wayfinder.

P.P.P.S. Who might enjoy The Wisdom Wayfinder? You can simply forward the email to them. Thanks for your support.

Subscribe to the Newsletter

Join Max J Miller Blog and receive new online content directly in your inbox.

Recommended for Your Journey

Discover more inspiring reads that support your journey toward growth, purpose, and emotional well-being.

[044] The Finish-Line Fallacy

- Max J Miller